Before we start, be warned that this entry contains major spoilers for the film It Comes At Night. In the past, I have discussed the plot details of numerous feature films quite freely on The Spirochaete Trail, although seldom any as recent as this, and as such I feel honour-bound to emphasise right from the go that we'll be wading through serious spoiler territory here. If you haven't seen It Comes At Night and wish to keep your experience fresh, you'd best be clicking your way out post-haste.

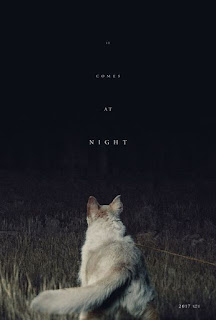

Among other things, It Comes At Night, the sophomore film of Krisha-director Trey Edward Shults, was an exercise in how deceptively one could package a feature to make it look like a completely different beast altogether. Audiences who flocked to their local theatres the in summer of 2017 expecting a good old-fashioned horror flick about a family being menaced by a strange nocturnal entity were sorely disappointed to instead receive a small-scale domestic drama (albeit one set in a post-apocalyptic landscape) about a couple of families bickering. The disparity between the film's critical reception and the audience reaction (it currently sits at 88% on Rotten Tomatoes, but earned a D grade from CinemaScore) would suggest that the latter weren't too impressed by this act of bait-and-switch (I can sympathise with that, for I have not forgotten the sheer embarrassment of attending a screening of M Night Shyamalan's The Village, which made a similar gambit, back in 2004). At the heart of the problem is Shults' rather befuddling choice of title, which to the rookie oozes intrigue, but may leave those who have seen the film scratching their heads, or else thumping their fists in frustration - at the very least, it's hard not to come away with the impression that Shults conceived the title before he'd fully ironed out the details of his story. What, precisely, comes at night? Add that to the film's misleading marketing campaign, which hinted strongly at the supernatural but drew heavily from surreal dream sequences experienced by the lead character, and you had a feature all but guaranteed to leave a sour taste in the mouths of a good percentage of its viewers. Is Shults' film a work of fraud, a barrage of cheap tricks that promises much but delivers little, or is there actually a deeper puzzle here to be solved?

It Comes At Night concerns a family who live in seclusion in a house buried deep in the forest; a house that could easily pass for a reasonably cosy holiday home, aside from the ominously-coded red door which provides its only passage to and from the outside world. It becomes apparent that the family are actually surviving in a tiny, hidden pocket of a world where civilisation has crumbled following the outbreak of a highly infectious disease, the symptoms of which include heavy vomiting, furuncles forming in the skin and, most unnervingly, a blackening of the eyes. In the opening scene, parents Paul (Joel Edgerton) and Sarah (Carmen Ejogo) are at the point of having to euthanise the latter's father, Bud (David Pendleton), who has come down with the disease, an act in which their teenage son Travis (Kelvin Harrison Jr) is required to participate. In the aftermath, Travis is haunted by visions of his ailing grandfather, and seeks solace in the companionship of Bud's beloved dog, Stanley. Later, another family living in the vicinity - young parents Will (Christopher Abbott) and Kim (Riley Keough) and their five-year-old son Andrew (Griffin Robert Faulkner) - make their presence known and the two families form an uneasy alliance in which they all have share of the house in the hopes of being stronger together. The household obeys a strict set of rules, including that they never go out at night and do not go out in daylight unaccompanied. For a time this arrangement works, but when Stanley the dog becomes agitated about something in the woods and disappears chasing after it, only to later return at death's door, a chain of events is set in motion causing the alliance to break down. The characters begin to suspect that one of them may have brought the infection into the house, bringing tensions between the two families to a head and leading, inevitably, to tragedy. In the end, nothing in particular comes at night, and the only tangible external threat that manifests itself at any point are two unidentified men (Chase Joilet and Mick O'Rourke) who attack Paul and Will early on the film. There are no witches, zombies or demons lurking in these woods, just the ugliness of humanity under pressure.

There are no traditional monsters in It Comes At Night, although if you are determined to see one, then odds are that you probably will. I've seen some viewers propose that the characters are actually in the midst of a zombie apocalypse with no zombies in sight - that this is the true nature of the disease and why the family make a strict point of burning the bodies of the infected, and that the outside world is menaced by sleepwalking zombies on a nightly basis (my take: that's an awful stretch. It was always straightforward enough to me that the family burn bodies to prevent the spread of a highly infectious disease). Others insist that if you watch carefully enough, you can make out the ominous form of a distinctly non-human creature lurking the backdrop during the sequence where Paul is driving away from the house with Will. I can see the appeal of this claim - it (allegedly) occurs during a moment where Paul's anxieties are fixed squarely on Will, the implication being that Paul is so preoccupied with whether or not he should trust this strange intruder that he fails to spot the actual monster lurking in plain sight. But I pooh-pooh it nonetheless. Unless Shults cares to confirm otherwise, I'm inclined to see this as another variation on the "munchkin suicide" legend that plagued The Wizard of Oz for many decades. People see a monster through the power of suggestion, not because there's actually a monster there. Having studied the moment in question closely in slo-mo, I'm confident that all we're actually seeing are the rotting remains of a dead tree. (Besides, if we are looking at "It" in this particular sequence, then It appears to be violating the rule made explicit in the title - more on that point later).

Nothing to see here.

In lieu of any literal monsters, our most logical explanation would be that the "It" of the title refers to something altogether less tangible, something nestled deep within our human nature. Perhaps it is all as simple as fear itself that comes at night, which seems borne out in Travis's darkest, most terrible fantasies taking on a monstrous life of their own whenever the lights go out. Some viewers have condemned the film's extensive focus on Travis's nightly fantasy life as one of Shults' biggest cheats, in that it provides him with enough spooky material to fill out a trailer and package the film as more traditional horror fare, while having little direct bearing on how the plot is resolved. In some cases, these fantasies might be seen as totals teases, hinting at plot directions that are otherwise left untouched. In one such sequence, Travis breaks the household's cardinal rule and goes outside at night in an effort to locate the missing Stanley, only to run into an object (unrevealed to the audience) of pure terror, yet the film isn't much interested in what lurks beyond the walls of the shelter at night, or in forcing the characters out to traverse this forbidden zone. We might have assumed that such a plot point was telegraphed early on when Paul stated that there are certain circumstances, "real emergencies", in which they might be made to go outside, but it does not occur. In a way, Travis's fantasy seems thrown in as a substitute for any actual representation of the outside world at night, which barely features at all - nearly all of the nocturnal scenes taken place within the confines of the domestic space, the drama deriving from the occupants' mutual suspicions of one another. For the most part, It Comes At Night does not go The Blair Witch Project route, in which the characters are menaced by a malignant presence that always keeps itself just slightly off of camera. By the end of the film, the very worst atrocities have been committed by the central cast on one another, and we are left pondering whether, if there did just happen to be something out there in the woods all along that had it in for these humans, it ever had to lift much of a finger (or equivalent appendage), for humankind will obligingly cannibalise itself given the right provocation.

Brian Tallerico, writing on RogerEbert.com, subscribes to this view when he calls It Comes At Night a "reverse horror film", one which holds a mirror up to the human psyche and proclaims that, no matter how terrifying the outside world might seem, "The real enemy is already inside. Now try and get some sleep." Truthfully (and as Tallerico himself notes), that in itself is not a particularly original or groundbreaking statement, for multiple horror films across the decades have contained variations on that very theme, even where there are very evident external threats to the characters. Stanley Kurbick's The Shining, which Shults has cited as one of the key inspirations for It Comes At Night (see below), leans heavily toward there being a supernatural presence menacing the Torrances (although the exact nature of that presence never makes itself clear), while containing the insinuation that Jack surrenders to the Overlook's bloodlust because it appeals to what was lurking in his nature all along - he's always been the caretaker, after all. Wes Craven's The Hills Have Eyes ends with one of its heroes contemplating, in wide-eyed horror, his own capacity for barbarism and violence. Characters in George A Romero films often wind up as zombie chow because human callousness and selfishness are the two great constants, even when the cannibalistic undead are scratching away at our doors. It is frequently the case in horror that we meet the enemy and it is us. In the case of It Comes At Night, whatever idle delusions we have about monsters lurking outside in the dark are complete red herrings - it's clear that Shults intends for us to take away that the real monsters were on the inside all along.

And yet something about that explanation doesn't quite add up. We are still led to believe that there is something lurking out there in forest, for what does Stanley the dog react to? Some viewers have argued that this is nothing more than an example of Shults presenting the characters and the viewers with an everyday occurrence and prompting their imaginations to run wild with them simply because they do not see the whole picture ie: the cause of Stanley's mania could be as mundane as the dog noticing a chipmunk in the woods and being compelled to chase it. Yet that does not satisfy, for we know from observing the dog's behaviours elsewhere in the film that Stanley's display of extreme agitation is implied to be uncharacteristic of him. For most of the film, Stanley is a docile beast who stays peacefully put at Travis's side. When he attempts to bark out during Will's intrusion, Travis is able to subdue him with relative ease. Here, Paul attempts to silence him and is bitten. Whatever Stanley sees the woodlands clearly has him very worked up. Not to mention, once Stanley disappears from view he falls abruptly silent. If he was felled by another animal, we would expect to hear some evidence of a two-way struggle. Ultimately, I think this is what many viewers have found unsatisfying about It Comes At Night. It appears to be looking to have it both ways, in being slyly subversive about the nature of its monster, while at the same time goading the viewer to believe that there might be a literal monster after all. Of course, if that is the case then this monster has very little bearing on the film's resolution - once the dog comes back, the possibility of there being something more in the woods isn't touched on again. In this interview with Slate, Shults talks about how he deliberately set out to make a film which avoids providing the viewer with a full set of answers, remarking that: "The storytelling in the film is very deliberate, and what’s in there is intentional, and what’s not in there is intentional." What Shults considers a deliberate lack of answers might in practice seem like little more than narrative messiness, however. You might be inclined to dismiss the end-product, as Tim Brayton does in his review on Alternate Ending, as an exercise in sneering vacuousness, a film that "loudly parades how much information it's not giving us, and then acts all smug and superior at the idea that some kind of audience might want answers, well that's just so plebeian, isn't it."

What the dog saw.

To me, the most revealing part of the aforementioned Slate interview is at the very end, when Shults brings up Room 237, the feature documentary from The S From Hell director Rodney Ascher on the range of ideas and theories that people have taken away from The Shining. Are the plot consistencies of It Comes At Night deliberately implemented in a self-conscious effort to manufacture the same kind of loopy conjecture that had people linking Kubrick's oblique horror classic to moon landing conspiracies and minotaurs, among other things? At any rate, it is evident that Shults is a great admirer of The Shining. It Comes At Night borrows a number of key elements from Kubrick's film - the son tormented by nightmarish visions, the ominous door that stands (ostensibly) between civilisation and chaos, the family unit torn apart by an increasing toxicity that gives way to murderous impulses. Nevertheless, due to its small scope and slow burning atmosphere, It Comes At Night found itself most widely compared to a much more recent horror; Robert Eggers' 2015 film The VVitch, which also deals with the failures of a family unit - in this case, a family living in isolation in 17th century New England - to survive in the face of impending catastrophe. The family grapples with demons, both internal and external, with adolescent daughter Thomasin (Anya Taylor-Joy) serving as the scapegoat for her family's woes (meanwhile, the family's actual goat, Black Phillip, serves a very different purpose). Unlike It Comes At Night, The VVitch makes it clear from the beginning that there are dark forces in the wilds that go beyond the family's understanding - we know that the gleaming, malevolent eyes of the forest are trailed on the family the entire time, in all its assorted forms (crows, hares, eerie female figures), but much of the drama arises from the family's preoccupations with what lies deep within their own tormented souls, the perceived sinfulness they see as ever-poised to devour them. When family patriarch William (Ralph Ineson) assures his eldest son Caleb (Harvey Scrimshaw), with barely-concealed desperation, that, "We will conquer this wilderness; it will not consume us!", he refers not the untamed land around them but to the wilderness of human nature, with its unending labyrinth of temptations and frailties. Whenever William feels overwhelmed by his human inadequacies, he seeks to reassert his control by grinding his axe furiously against pile upon pile of wood, a task as interminable as it is futile. Caleb, who is entering his early adolescence, is only now having to confront this struggle for himself, not merely in contending with his mother's distress at the thought of where his deceased, unbaptized younger brother Samuel will spend eternity, but in the awareness that his parents' zealotry is at odds with his own newly-emerging desires - namely, his incestuous stirrings toward his older sister Thomasin. Caleb desires Thomasin purely because, banished from the rest of society, she is the only available outlet for his pubescent fantasies. It Comes At Night also deals with the awakening of adolescent sexuality, although it appears to have come much later in life for Travis, who is already seventeen by the time his own latent urges are satisfied with the arrival of Kim.

Travis is alone among his own kin in relishing the alliance with Will and his family as an opportunity to expand his personal relations. It is Sarah who suggests the alliance, but she cites entirely self-serving reasons for doing so and it is evident that her true objective is to hold Will and company captive so that they cannot reveal their location to other outsiders. Paul, meanwhile, never loses his mistrust of Will, whom he suspects has not been entirely truthful about his family's circumstances (as it turns out, he has not, although we're never given sufficient evidence that Will's agenda is in any way sinister). By contrast, Travis is a fundamentally nurturing soul - we see this early on in the film when he assures Stanley, who has survived his master Bud, that he will take care of him, and he is later all-too eager to assume the role of an older brother figure to Andrew. And yet there is a duality to Travis's character that is not always easily consolidated - he is both a frightened victim whose fear of the unknown provides an outlet for the audience's own anxieties, and a stealthy prowler who enjoys a disquietingly voyeuristic relationship with the newly-arrived couple. Initially, Travis's tendency to eavesdrop on Will and Kim appears to stem from an innocent fascination with a family unit who are still ripe for the world, his own parents having long lost their own spark, as is evident in the rather more chaste, muted interactions between Sarah and Paul. Travis laughs along with Will and Kim's two-way jibing as if he too is a participant in the family's dynamics. Come nightfall, and a glimpse into Travis's dream life reveals a very different story - the camera stalks its way down the darkened corridor and steals an unsolicited glimpse into the neighbouring family's bedroom, where we find Andrew sleeping in solitude amid the tell-tale strains of the young couple making love in their bathroom. Travis's attempts to appropriate their love life for his own sexual fantasies are immediately disturbed; he envisions Kim in the bedroom with him, but when she leans over to kiss him a pool of blood trickles from her mouth and onto Travis's lips. The association between sex and disease plays like the punchline to a public information film about the dangers of STDs; exposure to sexual activity is alien to Travis, his youthful curiosity tempered by his anxieties regarding the consequences. For an open door has the potential to invite intrusion along with opportunity.

A popular interpretation of the film's cryptic title is that the "it" that comes at night refers specifically to Travis's ghoulish visions, yet Travis spends a good portion of his night not actually dreaming but wandering in a state of restless insomnia, the results of which are generally far more banal than anything he can imagine. Following his disastrous attempts at masturbatory fantasy, Travis wanders into the kitchen and has an encounter with Kim for real (tellingly, she is initially quite terrified to find him there), and the two of them share an almost painfully mundane discussion about party food preferences. Kim speaks of luxuries presumably long gone in this world - red velvet cupcakes, bread pudding and ice cream - none of which Travis, who does not have a sweet tooth, finds in any way tempting. The most revealing aspect of their dialogue is that both of these relatively young characters can plainly recall a time in which sweet treats were plentiful - we never gain a clear idea as to how long Travis and his family have been hiding out in the woods, but all clues point toward the fall of civilisation being a relatively recent occurrence. When Kim gets too relaxed, she becomes aware that her nocturnal companion is ogling her and this puts an awkward stop to their fond reminiscences. This deliberately dull scene is the culmination of Travis's sexual desires for Kim, for it does not have any impact on what happens in the film's climax. Perhaps this is yet another of Shults' red herrings - we anticipate that Travis's unclean fascination with Kim's physicality might lead to some form of contact between the two, and with it the spread of disease, when it transpires to be Travis's entirely innocent and nurturing relationship with Andrew that seals both families' fates, in another scene that plays out entirely banally given its appalling consequences. Which adoptive brother contracted the disease first and passed it onto the other is not made clear and this perhaps would not make a lot of difference either way - the insinuation that a member of one family may have let the virus in and introduced it to the adjacent family is enough to bring an end to the alliance and cause the families to revert to basic tribalism. As an audience, we are inclined to accept Travis's account because we have spent the duration of the film identifying with his fears and anxieties. But should we? Is this actually Shults' greatest sleight of hand? Is it perhaps a case of Andrew being scapegoated because, unlike Travis, he is too young to articulate a defense?

The Blu-ray commentary track with Shults and Harrison sheds little light on the film's central mysteries, with one exception - Shults explicitly states that he intended for the two mysterious men who attack Paul and Will to be a father and son, and hoped that the viewer would pick up on this by noting the physical similarities between the two. There are two implications he hoped we would draw from this. Firstly, that there are no real villains in this film, just desperate individuals struggling to survive and each with their own specific sets of loyalties. Secondly, although this is never explicitly raised in the film itself, Shults makes it clear that he intends for the viewer to consider the casting decision to have the main family consist of a Caucasian father and an African American son and, from that, to question if Travis is actually meant to be Paul's biological son. Given that this particular point seems pretty incidental to how events in the film play out, we might ponder just what effect Shults is gunning for. Does it have a significant impact in terms of how we perceive the characters? Obviously, the theme of family is an important one, for it determines where the characters' loyalties fundamentally lie when the chips are down. When it becomes apparent that one of the household may have let the sickness in, the two families agree to split up and quarantine themselves for a couple of days, ostensibly as a safety precaution, although what they are effectively doing is reaffirming the divide that has persisted between them all this while. Travis, who was by far the most willing to accept the newcomers as extensions to his own family, is appalled when Paul and Sarah decide that their only option is to purge the household of these now-inconvenient guests. Travis is less willing to yield his humanity than either of his parents, although the real source of his anxieties is made explicit when he laments feebly that, "If they're sick, I'm sick too", an implication that Paul and Sarah seem all too happy to ignore while there is an opposing family in the vicinity to be eliminated.

Paul, sensing that Travis was becoming too complacent around Will and co, had earlier attempted to instill in him the mantra that he could not trust anybody outside of his own family. But to what definition of family does Paul refer? Clearly, he would not accept Will's assertion that the deceased brother he'd mentioned previously was actually a brother-in-law with whom he was especially tight. If one's life-and-death loyalties are to be governed strictly by blood relationships, then the suggestion that Paul and Travis might not be related serves only to muddy the situation, and to accentuate the extent of Travis's anxieties. In a world where law and order are as distant and faded as Kim's red velvet cupcakes, anyone who falls outside of one's clan is considered fair game for eradication if they threaten the security of those within. This is tribalism 101. Travis's greatest fear, and the fear we see underpinning his persistent nightly visions, is not the fear of The Other but of becoming The Other. Travis is less afraid of whatever might be lurking outside the house at night than he is the mounting realisation that he is perhaps no safer where he is. He has already observed through the fate of his grandfather Bud that there are limits to how far one's own flesh and blood will be willing to stand by you if your identity as a member of the clan has eroded beyond recognition. Of course, Bud's condition is such that we are inclined to view his destruction at the hands of Paul and Travis as an act of mercy from a loving family, but when Sarah's parting words to her decaying father are echoed at the end of the film (this time addressed to Travis) it takes on a far more horrifying resonance.

It is here that we might consider the significance of Shults' decision to make one of the hallmarks of the disease a blackening of the eyes. This allows for dramatic tension when Kim instructs Andrew to keep his eyes closed during the final confrontation (to conceal his sickness, or because she recognises that the situation has the potential to get incredibly ugly and wishes to spare her son the trauma?). More crucially, it signifies a loss of humanity, or at least the perception of such. The blackened eyes give the infected a genuinely monstrous appearance, one which accounts for why the assumption that they are turning into zombies should be such a persuasive one, despite a general lack of evidence that they are in any way dangerous beyond their ability to pass on their sickness to others. And yet the most woeful indicators of a lost humanity arise from the acts of two characters who've yet to display any symptoms of illness - when Paul and Sarah force Will and his family out into the woods and destroy them one by one. Attentive viewers may notice that Shults deploys some curious sonic and visual tricks in this sequence - previously, Travis's nightmares were distinguished from reality through use of an anamorphic lens, which causes the aspect ratio to go from 2.40:1 to 2.75:1 (the idea being that Travis's world becomes more boxed in and claustrophobic as he gets more closely acquainted with his innermost demons), and given their own leitmotif. Both the leitmotif and the altered aspect ratios feature in the film's climactic bloodbath - a signal that Shults wants us to question the reality of what we are seeing or, more likely, that Travis's very worst nightmares have now been realised. The monstrous compulsions that he dreaded have been lurking in his parents all along have erupted in full fury, and Travis can no longer pretend that the individuals in whom he has placed his trust will protect him. When Sarah addresses a sickly Travis in the aftermath, his vision, now deep in the throes of fever, distorts her facial features into a grotesque caricature, for he no longer recognises her as the benefactor he knew. These are the monsters that have been lying in wait the whole time, beyond the line that has incontestably been crossed between civility and barbarism. All the same, when the credits roll we are still left grappling with that fundamental question - what, exactly, was coming at night in all of this? The horrors of the human psyche don't quite seem to fit as our answer.

In the end, the greatest curiosity about Shults' concoction is less that nothing in particular comes at night, despite the promises of the title, but that very little of the horror therein occurs in the nocturnal hours at all (Travis's troubled fantasy life notwithstanding). The majority of the film's genuine horrors - the encounter with the two mysterious men, Stanley's inexplicable disappearance, the final grisly execution of Will and his family - take place in broad daylight, the only notable exception being Stanley's unceremonious return from the wilds. For the most part, night is simply an empty space to be filled, a vacuum onto which Travis's most gut-wrenching anxieties are projected. There is nothing out there in the dark, and that nothingness is precisely what makes the film's nocturnal world so oppressive. Confined and alone, Travis is left to simmer in every last inch of his unease - his guilt, his paranoia, his morbid curiosity - and finds himself caught between two different very different extremes: the worst of what his imagination has to offer, and the stifling monotony of his insomnia.

Ultimately, the film to which I feel most inclined to compare It Comes At Night is not The VVitch or The Shining but The Turin Horse (2011), a slow-burning apocalyptic drama from Hungarian directors Bela Tarr and Agnes Hranitzky. The Turin Horse is horror cinema played at the most muted and low-key level possible; a film in which terrors are derived not from the spookhouse but from the leaden monotony of routine and the bleakness of a waning Earth that isn't going out with a bang so much as grinding to a gradual, emaciated halt. Again, our characters are a small secluded family unit, this time consisting of just a a father (Janos Derzsi) and his daughter (Erika Bok), as they attempt to eke out a living across the last six days of planet Earth, almost defiantly going around their business as the world around them slowly unravels in decay. As with It Comes At Night, it is the family's four-legged companion, the titular horse, around whom their living and daily routine indispensably depends, that seems most attuned to the horrors of their existence. The horse loses interest in living long before the humans gain an inkling of what they are up against, spending much of the 146 minute running time locked away in its stable and passively deteriorating, as if in quiet protest at its masters' insistence on going about the same oppressive labours day in and day out. Like The Turin Horse, It Comes At Night depicts The End of Times from the perspective of a family unit out in the middle of nowhere, clinging desperately to their way of living while the rest of the world disintegrates. Their life is a similarly arduous one, but they have managed to keep themselves afloat all this time by adhering to a strict set of rules and procedures. In both cases, we might wonder, as appears to have occurred to the titular Turin horse, just what the point in continuing is, when the The End is looming so frighteningly close; it is an extortionate amount of effort for what is certain to be a losing battle. And yet, the characters keep going, for no other reason than that their hard-wired impulsion toward survival will not allow them to cease. As long as there is another day, and more time in which to fill, the characters essentially have no choice but to carry on with their oppressive daily (and nightly) rhythms. Perhaps The End, when it finally arrives, will come as a relief.

Mutter, ich bin dumm.

In both cases, the dawn of a new day brings a reprieve from the coming oblivion, a sign that the world has not yet ended and darkness has not yet taken a permanent hold, and that things must continue for at least one more diurnal cycle. But with this does not come solace. For the family in The Turin Horse, another day means having to go about their laborious grind all over again. For the cast of It Comes At Night, making it through that cold nocturnal void means having to spend the daylights hours with something equally oppressive - a vast wilderness of trees that appears to stretch out into infinity, not so much concealing the occupants of the house from potential onlookers as keeping them boxed in and imprisoned. The trees become reminiscent of the bars of a steel cage, offering the characters nowhere to run other than into the jaws of a treacherous hinterland that threatens to engulf those all who disappear into it. If the characters, with the procedures and structure they abide by, represent the last dying flickers of human civilisation, the expansiveness of the woods is a reminder that the chaotic wilds already have them surrounded and will one day see them completely extinguished; their opposition, though tenacious, is ultimately futile. The innumerable trees are frightening because, much like the dark, they have the potential to conceal what is out there. But for the most part, there does not appear to be anything out there to conceal; the woods, like the dark, are characterised predominantly by a dead, eerie stillness. Once again, we find ourselves returning to the question of what Stanley the dog reacted to. And the answer, yet again, might indeed be nothing. In the end, it might be enough to assume that Stanley goes mad because the world is mad - his final outburst a less passive variation on the Turin horse's refusal to go along with its masters' drudgery. Stanley flees into the woods as an act of self-destructive surrender, an act which follows on immediately after Paul's efforts to imprint on Travis that Will and his family's Other status makes them inherently unworthy of trust. It is as if Paul's words alone are enough to seal the fates of both families.

Originally, Shults had a very different ending in mind for his film, one in which all of Travis's visions would converge in a final apocalyptic blaze, but opted against it, wisely discerning that such a dramatic finale would not be befitting for such a quiet depiction of a world in terminal decline. Instead, the very last image shows Paul and Sarah sitting in total silence at their dining table, with a conspicuously empty space where Travis should be. The couple can no longer communicate or even make eye contact with one another, and we know that they too are not long for this world - already we see the signs of physical deterioration, betraying that their acts of brutality against Will and his family were all for naught. This scene deliberately mirrors one that comes closely after Bud's death at the beginning of the film, in which the remaining family members were shown gathered around the table, barely communicating but desperately attempting to hold together in the wake of their loss. They were clearly a family unit bent on survival. Now, only the skeletal fragments of that unit remain. This ending recalls the final images of The Turin Horse, in which the father and daughter are seen sitting at their table in darkness in the dying moments of the final day, the former feebly attempting to maintain what is left of their daily routine in the face of pending obliteration. He paws desperately a raw potato, lacking the resources to make it halfway palatable, insisting that they need to sustain themselves, even in a world of eternal darkness, although his daughter does not respond, apparently having realised that their horse had the correct idea all along. In the same way, when Paul and Sarah assume their established places at the table, it represents a feeble effort to adhere to their own routine, or at least what meagre pieces are left of it to be picked up. We recognise that this is all in vain. Their unity is destroyed; the notion of life being salvaged as to somewhat resemble how things were before is unimaginable. Eternal darkness has set in for them, although in a far less literal manner than has happened for the characters in The Turin Horse.

Where the final scene diverges from that of The Turin Horse, and from earlier sequences depicting the family's table routine, is that it takes place not in the darkness of an incoming evening, but in the harshness of day; in a move almost startling in contrast to the majority of the film's interior shots, we see brilliant bursts of light streaming from the backdrop as Paul and Sarah let out their waning breaths. This is the cruelest twist of Shults' film, one that even the characters of The Turin Horse, prolonged though their suffering has been, are ultimately spared. The cast of It Comes At Night have all along been tensing themselves for an oblivion that, though it is clearly inevitable, never actually arrives. Instead, the cycle continues in an almost taunting manner, goading these blatantly crushed and defeated figures to carry on for as long as it insists on going, any lingering hope of renewal already lying dead and buried alongside Travis and the others. We leave It Comes At Night, not with the embrace of eternal darkness, but with the dawning horrors of a brand new day.