Remember when I said that the cliff-hanger ending to Series1, episode 5 did little for me as a child because, even then, I knew full well

that truly major characters like Badger and Fox were never going to be killed

off? Well, guess what? They actually did kill off Badger in Series

2. In fairness, he wasn’t really so much

of a major character by this point. He’d

had an important arc in the winter portion of Series 2, when he was injured and

taken in by the Warden, but once the thaw arrived Badger became much more of a

side character – the focus switched mainly to Fox’s quarrel with the blue foxes

and the adventures of Fox’s son Bold upon leaving White Deer Park, and the

writers were clearly struggling to keep Badger relevant in all of this. So a complete and utter exit was the way to

go.

Actually, Badger’s death is quite a curious one in that,

unlike Mole’s death, it had no precedent in original novels (where, if I recall

correctly, Badger made it to the very last page). The series had absolutely no obligation to

kill him off, and yet they did so anyway.

As noted, I suspect that Badger’s declining relevance in the post-winter

narrative was a significant factor, but I’d also speculate that Badger’s death

was intended to tie in with one of the dominant themes of Series 2, concerning

youth, aging and the gap between the older generations and the young. One of the key narrative questions deals with

whether or not the respective offspring of Fox and Scarface will choose to

continue the wars of their fathers, or if the new generation represents an

opportunity for peace and renewal. While

Friendly (who really wasn’t) sides very firmly with his father, Fox runs into

conflict with Bold and Charmer, who each have their differing perspectives upon

the feud with Scarface and how best to approach it.

The altercations between Fox and Bold get so nasty that Bold chooses to

disown his father altogether and live outside of White Deer Park. Fox later accuses Charmer of treachery when

he learns that she and Scarface's son Ranger are secretly on friendly terms, and observes that

“the young don’t seem to honour the Oath as we did.” Badger’s death, however, prompts Fox to

reflect upon his own waning youth and his need to learn how to grow old

gracefully. In that sense, it’s a much

more meditative death than was typical for the series (I’ve acknowledged that,

in Series 1 in particular, death was simply a nasty fact of life for the

Farthing Wood animals, and they generally didn’t have time to dwell upon it any

more deeply than that) and it did enable a nice moment of contemplation between

Fox and Vixen.

All the same, I get the impression that the production team

rather regretted their decision to kill off Badger come Series 3, because they

introduced a new badger character, Hurkel, who was clearly designed to be his

replacement (or, at the very least, to enable the series to keep alive its

iconic imagery of a badger carrying a mole on its back, as Mossy was seldom far

from him). Shadow, a female badger

introduced in Series 2 during Bold’s arc, was likewise solidified as part of

the main cast in Series 3 in order to fill a few of the roles that were Badger’s

in the last couple of novels (such as getting sick after drinking poisoned

water). I’ve mentioned earlier that I

didn’t much care for Series 3 and I don’t want to labour that point too much,

but I found Hurkel to be one of the most thoroughly unappealing characters that the show

had to offer. Meanwhile, the decision to have Shadow return as a main character reeked

of the kind of “they were popular, let’s have more of them” mentality that

made the third series feel like the product of extensive focus group-led

retooling (though Rollo was an even more disastrous example). When Badger died, he left a void in the

series that could truly never be filled.

Oh, and as I’ve alluded elsewhere, I suspect that Mole’s death

was shifted forward from where it occurs in the books in anticipation of Badger’s

death. If Badger had been the first to

go then there would have been no way to have included the whole aspect of him mistaking

Mossy for his father. Mole’s exit and

Mossy’s entrance also fit in nicely with the series' wider themes of birth, death, aging and renewal.

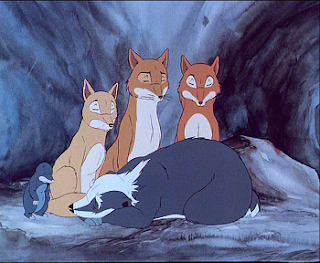

Shortly before Badger’s death, Fox had managed to alienate

him by verbally attacking him when Badger had suggested that the two of them

were getting past being able to deal with Scarface (the result of misinterpreting a statement made by Vixen). As a

result, Badger hasn’t been spending a lot of time with Fox lately. Mossy goes to visit to him in his sett, to

find Badger in a somewhat listless state, although he does respond to Mossy and

greet him as “Mole”. Mossy seems quite

prepared to drop the deception altogether at this point and confesses to Badger that

he’s not really Mole, but realises that Badger isn’t completely with

it. Disturbingly, he’s rambling about

being back in Farthing Wood with his long-departed family, which can't be a good sign. As he continues, he seems to forget about

Mole altogether and speaks only of his badger ancestors.

Horrified, Mossy hurries to Fox, Vixen and Friendly and

informs them that Badger may not have much time left. The four animals head back to Badger who,

still recognising Fox, assumes that he’s there to persuade him to leave his

home and his family in Farthing Wood, which he refuses to do. Fox attempts to make his peace with Badger

before it’s too late and apologies for his recent unkindness. This prompts Badger to deliver his

haunting last words: “A fox worried about kindness? I must be in Heaven.” With that, Badger chuckles to himself and

finally passes away.

HORROR FACTOR: 5. This death certainly came as a shock to those

viewers who had read the books in advance and assumed that Badger's immortality was guaranteed,

though as Farthing Wood deaths go it was easily one of the most peaceful.

NOBILITY FACTOR: 10. Badger’s time had simply come.

TEAR-JERKER FACTOR: 10. Apologies to all you Bold fans

out there, but for my money this is easily the most heart-breaking death of the entire

series. They went all-out in assaulting

the heartstrings with this one and by jove, they succeeded. I sob my eyes out every time.

RATING: 25