Saturday, 28 April 2018

Crudely Drawn Filler Material: The Simpsons in "Bart and Dad Eat Dinner" (November 1, 1987)

First off, make a note of that title. This short is called "Bart and Dad Eat Dinner", not "Bart and Homer Eat Dinner". You might recall a moment in the episode "The Simpsons 138th Episode Spectacular" where Troy McClure quips that the Simpsons children "were no match for Captain Wacky...later renamed Homer" and, well, there is a small kernel of truth in that bizarre statement. Homer was, sorry to report, never officially named Captain Wacky. But he wasn't always officially Homer. While creator Matt Groening had always envisioned the character as being named as such (Homer was named in honour of Groening's own father), Homer's name was not officially revealed to the viewer until quite late on in the Ullman shorts' run, when he was reprimanded by his own father, Abe Simpson (then just officially "Grampa Simpson"), in the 30th short, "Shut Up, Simpsons". Prior to that, he was just plain old "Dad" or, on more formal occasions, "Mr Simpson". According to Warren Martyn and Adrian Wood, authors of I Can't Believe It's An Unofficial Simpsons Guide, (who aren't always the most reliable source when it comes to Simpsons information, mind), Marge was never actually addressed as "Marge" at any point throughout the Ullman shorts. I haven't gone through the shorts with a fine enough comb to say for sure if that's true, but for now I'm happy to take their word for it.

That neither Homer or Marge were afforded proper names for the better part of the Ullman shorts' run is indicative of just how heavily focused they were on the younger Simpsons' perspective. In fact, reviewing the full list of Ullman shorts, it stands out to me that there are no shorts focusing exclusively on Marge and Homer. The closest we got were shorts such as "Dinnertime", which centred on the relationship dynamics between the adult Simpsons, but always within the context of the precedents they were setting for their offspring. A good chuck of the shorts thrived on the disconnect between the Simpsons generations, with Bart, Lisa and Maggie routinely challenging and questioning Homer and Marge's adult authority. In particular, there were numerous shorts examining the relationship Bart and Homer, as no other pairing illustrated this generational tension more adroitly (partly because Lisa's character was still something of a blank slate at this point, so there wasn't quite so much to be milked from her own individual regard for her elders, and Maggie's muteness made her rather more limited). In the Ullman shorts, Homer was constantly striving to be a strong male role model to his son, while Bart, smart enough to see through his father's buffoonery, responded with a yearning for rebellion but also unease, as if aware that he was staring at his potential future self and where he might be headed if he were to emulate Homer's shaky example. "Bart and Dad Make Dinner" explores this unease, using the relatively simple scenario of Bart being made to spend an entire evening at the mercy of his father's lack of sophistication.

Here, we see what happens when Marge isn't around and care giving responsibilities fall exclusively to Homer. With Marge and the girls having disappeared to the ballet for the evening, it's up to Homer to prepare dinner for Bart and himself. Alas, he clearly does not have the skills to recreate the full dining experience seen in "Dinnertime", so dinner a la Homer consists of setting up the TV tables and selecting from two varieties of pre-prepared meals - fish nuggets and pork-aroni - which Homer has the bright idea to combine into a single unpalatable mess (in fairness, it doesn't look any less unappetising than the unidentified purple mush prepared by Marge in "Dinnertime", but I could buy that that was at least halfway nutritious). His dubious culinary practices aside, Homer does do a fairly competent job in Marge's absence, telling us that, when it came to upholding basic household routines, he wasn't a complete lost cause at this stage in his character's lifetime - compare this to the Season 8 episode "Bart After Dark" from the series proper, in which Bart and Homer had the house to themselves and, in lieu of brushing his teeth, Homer had Bart rinse his mouth out with soda, and you'll see just how drastically he had degenerated over the course of nine years.

"Bart and Dad Eat Dinner" might also contain one of our earliest hints of Lisa's intellectual mettle, given that she's chosen to attend the ballet with Marge over roughhousing it with the boys. Then again, maybe this a simple gender divide, with ballet being touted as the kind of stereotypically feminine activity that only the Simpson women would be likely to vacate the house for (as Patty Bouvier once said of ballet, "That's girls' stuff!"). All the same, there's a definite tension in this short between high and low culture, aptly illustrated by the prospect of an evening spent either watching ballet or downing unappealing TV dinners. Bart, reluctant to follow his father down the rabbit hole of junk culture, realises too late that he made the wrong decision in passing up an evening of ballet and is left to ponder the degenerative effects of a ready meal diet, observing that Homer's brutish behaviours appear more canine than human.

Of course, one of the greatest strengths of The Simpsons was in how it deftly revealed the underlying unity that kept this rowdy pack of feral suburbanites afloat, and the short does end on a moment of connection between Bart and Homer. Marge returns home after a divine evening of ballet to find both Simpsons males zoned out on the couch. While their comatose murmurings betray vastly different perspectives on the overall pleasurableness of an evening spent in one another's company, our final image is one of affinity, with the mutually exhausted Bart and Homer lying and snoring in perfect harmony, each as artlessly oblivious as the other. Bart is truly his father's son, whether he's universally thankful for that fact or not.

Finally, eagle-eyed viewers might have picked up on a surreal background gag involving the boat painting hanging above the Simpsons' couch. Pay close attention at the start of the short and you'll notice that depicts not the serenely drifting vessel familiar to viewers of the series proper, but a scene of impending disaster, with an iceberg lying directly in the boat's path. In the third act, we can see that the boat has struck the iceberg and is now going down in a terrible smoking wreck with god knows how many souls on board. Finally, in the fourth act, the painting shows a bleak image, with the ship completely submerged and only a few isolated pieces of debris remaining atop the ocean. This is exactly the kind of outlandish japery that The Simpsons would shift away from as it developed and cemented its identity as a more realism-orientated cartoon, but here it taps in perfectly to the stranger, more perverse vein evident in the earlier Ullman shorts. Perhaps the morbid visual motif of a boat slowly succumbing to the savagery of the ocean was the shorts' way of underscoring the off-kilter nature of the Simpsons' first outings, back when their freakishness was still an integral component of the family's aesthetic. In the series proper, any surreal tinkering with the background boat would be a tactic reserved strictly for Halloween episodes.

(Note: A similar gag actually occurred in "Dinner Time" too, with a completely different scenario of death and destruction - there, an ostensibly picturesque mountain was transformed into an erupting volcano over the course of the short. Despite the roughness of the animation, it blatantly paid to have an eye for detail with these shorts).

Friday, 27 April 2018

Crudely Drawn Filler Material: The Simpsons in "Dinnertime" (July 12, 1987)

Following their savage deconstruction of parent-child bedtime interactions, it was only a matter of time before The Simpsons moved onto taking down another much-revered family ritual - the twice (or thrice) daily gathering around the table for a good old-fashioned social binging. Whereas "Good Night" dealt with the failures of the adult Simpsons to instill a sense of nocturnal domestic security in their impressionable offspring, "Dinnertime" looks at their failure to model basic etiquette, in part due to their own inability to work from the same page. The animation in "Dinnertime" is still extremely crude, although it had evolved considerably since the eye-popping scrappiness of "Good Night", with the family now starting to look more like their familiar selves and Marge's trademark beehive hairstyle beginning to scale its full dizzying heights. In "Dinnertime" we also see Homer and Marge's respective personalities beginning to sharpen - although ostensibly the short deals with Marge's uphill crusade against her family's collectively hideous table manners, it is effectively about the relationship between Marge and Homer; the kids are present, but they get next to no dialogue here. I noted in my review of "Good Night" that Homer's characterisation was somewhat different in the Ullman shorts, for he was a notch more conscientious when it came to keeping his family in order, although right from the start his basic underlying gag was always that he was never too outstanding a role model, partly because was something of an oafish brute, but mostly because, at heart, he was fundamentally one of the kids himself. Meanwhile, Marge had the burden of being the sole responsible adult in the family (Lisa would eventually assume a wisdom and maturity beyond her years, but at this stage she was still an unruly hellion herself). "Dinnertime" offers a glimpse into the dynamics of their lopsided marriage, demonstrating both Homer's crippling lack of self-awareness (although at this stage in Homer's character development, it's not entirely clear if he's being deliberately flippant or if "Good drink! Good meat! Good god, let's eat!" really is his idea of reverence) and the endless frustration and disappointment nestled beneath Marge's thankless daily grind (Marge was always the emotional glue holding the family together, and "Dinnertime" cements that her talents were doomed to be eternally unappreciated).

"Dinnertime" was the last Simpsons short of Season 1. Meaning that in that alternate universe where The Tracey Ullman Show stuck with Dr N!Godatu as its sole commercial bumper, this is where the family would have ended their run. In that regard, we might view the closing moments to "Dinnertime" as the punchline to not merely this particular slice of Simpsons life, but also to the entire conceit of The Simpsons in their most primitive state. In the fourth act, Marge makes one final perfunctory effort to push her barbaric family, their mouths too clogged up with food to be capable of forming words, one step closer to civility by feebly attempting to initiate a conversation, only for Homer to take this as his cue to have Bart wheel in the TV. The appearance of the chattering cyclops effectively shuts down whatever hopes Marge might have had of genuine interaction with her family (although perhaps this is indeed what she expected - I notice that Marge doesn't seem particularly perturbed when Bart produces the TV). The real punchline, however is to be found in the overheard dialogue coming from the newscast as the short fades out and the television brings in a disturbance all of its own:

"On tonight's news, bus plunge kills 43. Freak roller-coaster accident decapitates..."

Obviously, those are some fucked up news headlines right there.

For the first season of The Tracey Ullman Show, the shorts never ventured beyond the walls of the Simpson household, giving exclusive attention to the family's domestic sphere and the day-to-day chaos which characterised the most ostensibly banal of their activities. The television at the end of "Dinnertime" offers our first fleeting window into the outside world, the gag being that the Simpsons are merely the tip of the iceberg in a universe defined by chaos and the frightening capriciousness with which it dishes out death and destruction. This isn't the first time in which we've seen just how integral the television set is to the family's daily life; this was the focus of the second Ullman short, "Watching TV", in which the box was depicted as a never-ending source of blaring light and moronic jingles, underscoring the mindlessness of the three-way struggle between Bart, Lisa and Maggie to exercise control over the channel-selector dial. "Dinnertime" also explores the effects of 24-hour media saturation, alluding to the paradoxical manner in which it bombards us with images of carnage, heightening our day-to-day anxieties about the world we live in while also eroding our shock at the ubiquity of said carnage and encouraging us to revel in the spectacle, as reflected in the nonchalance with which every family member but Marge regards the ridiculously macabre news headlines. We've spent the past seven shorts gawking at this barely-human family as they slob around in their natural habitat, but at the end of "Dinnertime" the tables are essentially turned, as the Simpsons break from their domestic wilderness and look to the wider world for escape and enlightenment, to find only a sickening abyss gazing back at them.

Oh, and for a short centred around the revolting eating habits of freaky neon demons, "Dinnertime" has fewer stomach-churning visuals than one might expect, although I do find myself eyeballing with suspicion the rather unappetising-looking mush that Marge has prepared. Like, what the hell is it? It's purple! How many savoury dishes are there that are purple? I guess it could have beetroot as a primary ingredient, but why is is moving around by itself in the opening scene? Is it just an example of the weird early Ullman short animation, or are they attempting some kind of surreal sight gag in which the purple foodstuff is somehow alive? Either way, it's creepy.

Monday, 23 April 2018

Crudely Drawn Filler Material: The Simpsons in "Good Night" (April 19, 1987)

It's been said that we'll either die heroes or live long enough to see ourselves become the villains. The internet tells me that this particular saying is to be attributed to Aaron Eckhart's character in Christopher Nolan's The Dark Knight (2008), although funnily enough I could have sworn that it went back a lot further than that. Ah well, regardless of who first said it, it's a phrase I've been considering a lot in relation to The Simpsons over the past...couple of weeks or so. The Simpsons has been running for just shy of three decades now. It's been part of the cultural landscape for so long that it's easy to forget just how wildly explosive a concept it was when it debuted. When The Simpsons was first starting out, it WAS the rebellion. It was rude, punk and subversive. It made the kinds of honest observations about the modern American family that its live action contemporaries were reluctant to partake in. Adults who were not uniformly good role models, kids who did not unconditionally respect their elders; the series caught on because audiences could identify so many of their own weaknesses and indiscretions in these vulgar yellow demons, to a degree that caused discomfort among some circles back in the day. When George H. W. Bush proclaimed, "We're going to keep trying to strengthen the American family; to make them more like the Waltons and less like the Simpsons," it was a watershed moment for the series - few things say you've made it quite like the establishment publicly marking you out as a threat to everything it's built itself on. Nowadays The Simpsons IS the establishment; the kind of show that apparently sees fit to have its characters break the fourth wall to inform the viewer directly, and without a shred of ambiguity, that if they have a problem with the status quo then they should Shut The Fuck Up. When I reflect on the series' response to long-standing criticisms which have been coming more to the forefront of popular consciousness in recent months, I'm inclined to utilise another movie quote, this one spoken by Samuel L. Jackson's character in Jackie Brown (1997): "What the fuck happened to you, man? Shit, your ass used to be beautiful."

I've no desire to go any deeper into the whole Apu controversy for now (although I will happily go on record for saying that I think the series' response was, at best, staggeringly obtuse), but I can't help but contemplate, as I prepare to look over the very first piece of Simpsons media, the profound sadness I now feel in also having to view it from the perspective of where the series was eventually headed. For its past twenty years or so of life, the series has been subject a number of (not invalid) criticisms about its declining quality, as it continues to chug ever along, less out of a creative urge to gift the world with more Simpsons stories, we suspect, than that The Simpsons has been part of the cultural landscape for so long that its stubborn refusal to quit or disappear has become an integral part of its identity. But with this latest development we may have seen the series on the cusp of assuming a new identity, one altogether more sour and embittered at the word's failure to remain frozen in time as its characters have done. The Simpsons' days of being a rebellion were already long behind it, but only in recent days did we arrive at the point at which the series openly and willfully posited itself as the thing to be rebelled against - a series which the next generation of young comedy minds aspiring to see things change can look toward and think "I need to do better." The Simpsons has lived long enough to see itself become the villain.

So yeah, I start this entry on a somewhat more sombre note than I anticipated when I promised it back in January. There, I indicated that I intended to examine "Good Night" from the perspective of what pure, unadulterated nightmare fuel it is. In my idler moments, I try to put myself in the place of viewers who tuned into Fox on that fateful night of 19th April 1987, with no prior concept of who the Simpsons were or what to expect from them, and I invariably wonder how well many of them managed to sleep throughout the early hours of 20th April 1987, after what they had just witnessed. When I was first introduced to the Simpsons, in 1991, they were already stars of their own hit series and had a novelty dance track penned by Michael Jackson which was taking the school discos by storm, although any fan worth their salt knows that the family had far more humble origins on The Tracey Ullman Show, a comedy sketch show starring British comedian Tracey Ullman that ran from 1987 to 1990, and where Homer, Marge, Bart, Lisa and Maggie were regularly featured in a series of crudely-animated commercial bumpers (for simplicity's sake, I will be referring to them here as the Ullman shorts), before their big break arrived in late 1989. I find myself endlessly fascinated by the Ullman shorts, not simply from the standpoint that, as Simpsons buff, it's always interesting to go right back to the series' roots and chart how things developed, but because they show the family verging on an altogether stranger and freakier direction, one that was eventually abandoned as the concept was ironed out and lost its wrinkles. When The Simpsons first came into the world, it was an ugly beast - rough and primitive and dripping with visible afterbirth. The central gag - that the family were dysfunctional and their day-to-day existence was choc full of vulgar and chaotic moments - was deftly reflected in the sheer grotesqueness of those early shorts. They were an eye-searing anecdote to the blandly fuzzy sitcom families that were hogging the airwaves at around the same time (see Growing Pains, Full House and their ilk). This family were not warm or cutesy and for a lot of the time they barely even looked human. Matt Groening has never spoken too highly of his ability to recreate homo sapiens, which is why earlier on his cartooning career his signature characters were leporines. When he pitched the idea for The Simpsons to James L Brooks, it was literally a quickie he threw together in a last minute panic upon deciding not to surrender the rights to his rabbit-orientated strip, Life In Hell, to Fox. Groening didn't think much about the crudeness of the designs he submitted because he took it for granted that they would be tidied up during in the animation process; in actuality, the minute animation team at Klasky Csupo traced over Groening's original sketches, preserving that initial, splapdash primitiveness in all its uncanny glory. In many respects, the crudeness of those initial outings was the perfect accident.

The Simpson family featured in "Good Night" and other early Ullman shorts were not uniformly recognisable as the family that would later become fixtures of our Sunday night viewing, and not just because their appearance erred a tad more on the monstrous side. It's often said of the Ullman shorts that every family member had their familiar character traits right from the start apart from Lisa, who was initially nothing more than a female counterpart to Bart. That isn't strictly true, although in the earlier shorts Lisa was deployed primarily as Bart's foil; she and Bart had a mutually bratty sibling rivalry and there was little hint of the sensitive intellectual she would blossom into when the series proper took off (the decision to make Lisa a saxophonist was arguably the major turning point in defining her entire character). Homer's character was also a little different in the Ullman shorts - he was gruffer and angrier and he took his role as family patriarch a lot more seriously (even if he was never astoundingly good at it). The core voice cast was always the same, although like the animation it had to go through its own messy evolution process before arriving at its familiar state. Whereas Cartwright and Smith had Bart and Lisa's voices nailed pretty much straight off the bat, it took Castellanata and Kavner longer to grow into their respective roles, particularly Castellanata, who was initially doing Homer as a loose kind of Walter Matthau impersonation.

The first season of The Tracey Ullman Show had only seven Simpsons shorts out of a total of thirteen episodes - this is because the Simpsons initially had to share their limelight with another animated segment, Dr N!Godatu (created by National Lampoon cartoonist MK Brown), which took commercial bumper duties in alternate weeks. Dr N!Godatu had considerably less luck than The Simpsons and was ditched after the first season, giving Groening's creation free reign across Seasons 2 and 3 (the family were missing from the fourth and final season of The Tracey Ullman Show, for by then they had moved onto new and bigger things). When I'm not idly wondering about audience reactions to the very first Simpsons short, I'll wonder about that alternate universe in which The Simpsons and Dr N!Godatu's fortunes were reversed; where The Simpsons is now this obscure little footnote in animation history while Dr N!Godatu's wildly successful spin-off is pushing thirty and, just a couple of weeks ago, burned a chunk of goodwill with its odious response to questions about some of the outdated humour it had been preserving in amber since 1990.

For years, "Good Night" was one of the easiest Ullman shorts to track down, as it was featured in its entirety in the Season 7 Simpsons episode "The Simpsons 138th Episode Spectacular" and was later included as an extra in the Season 1 DVD box set. It's the kind of exposure which the remaining forty-seven Ullman shorts would surely kill for. As a kid, I desperately longed for a VHS release comprising the complete set of Ullman shorts and was frustrated that no such product existed. I deduced that I couldn't be the only Simpsons fan who was hungry to get acquainted with the family at their most primordial. When DVD box sets became the hot new thing I figured that it could only be a matter of time before they branched out into the Ullman shorts. But alas, that too remained a mere pipe dream. To date, the complete Ullman shorts have never been released on home media, and if Dame Rumour is correct, this is because Tracey Ullman herself was purposely holding onto them for a Tracey Ullman Show DVD release that never happened. By now, it seems safe to say that the Ullman shorts missed the boat in terms of getting a full release on physical media. The best we can reasonably hope for at this late stage would be for the shorts to be made available for streaming - there was talk about the Simpsons app, "Simpsons World", acquiring the rights to the shorts back in 2013, but no idea how that turned out. (Here's a better question - is the Simpsons World app still pushing that old non-canonical biographical information about Sideshow Bob's career pinnacle being a prison production of Evita? Make a note, because we seriously need to talk about that some time.)

Ah well, thank Heavens for YouTube, eh?

For the first two seasons of The Tracey Ullman Show, when The Simpsons segments were used as commercial bumpers, the shorts were broken down into four separate acts, each with their own individual punchline, and interspersed throughout the course of the episode - which accounts for their distinctly piecemeal nature when viewed in their entirety. By Season 3, the Simpsons had proven popular enough to be promoted to their own full slot (and featured in the opening credits sequence), and the shorts consisted of complete stories told in one go (with the exception of shorts 46 and 47, which told a two-part story, "Maggie In Peril"). "Good Night" takes advantage of the four act structure of the earlier shorts to gradually introduce the family members before having their individual arcs all converge in the final act. From the start, we see the Simpsons fulfilling their primary function as a subversion of traditional family ideals, with a perfectly banal ritual of parental devotion - parents tucking their kids in for the night - here getting a dour deconstruction as Bart, Lisa and Maggie spot the unintentionally nightmarish implications of Homer and Marge's bedtime bromides. The true irony of the piece lies in the outlandishly nightmarish energy that the Simpsons clan, as depicted here, themselves give off; we are, in effect, watching a bizarre cartoon in which quasi-monstrous beings are gripped by horrifying fantasies about what could be lurking in the darkened spaces within their own bedrooms (or, in Bart's case, inside his own ill-defined mind - the opening exchange between Bart and Homer is particularly interesting as it seems to suggest that the real bugbears to lose sleep over are to be found in the absurdities of human existence). You can say what you will about the animation in the very first Ullman shorts - it may have been crude as sin, but nowhere else in the family's run have the characters appeared so hypnotically, kaleidoscopically animated. Observe how the eye animation for each individual Simpson child acts as the the punchline to their their respective segments; the unique expressiveness with which those eyeballs writhe and squirm on being plunged into the dead oblivion of night, from the dizzied delirium in Bart's eyes to Lisa's fearful, darting pupils, to the sheer, unbridled terror emitting from Maggie's urgently convulsing peepers. There's a spunkiness to the proceedings which helps to overcome the limitations of the rough animation, and this is most evident during Maggie's segment, as Marge regales her impressionable infant daughter with that most ominous of lullabies, "Rock-a-bye Baby". We see a lot of very obvious looped animation going on in Maggie's fantasy, which nevertheless plays like a convincingly minimalist nightmare about the terrors of free-falling for all eternity (we never do see Maggie hit the ground, which only accentuates the horror).

Still, central to the entire conceit of The Simpsons was that these monstrous beings were never anything less than fundamentally human. When we reach the fourth act and get past the inevitable punchline (in which Homer and Marge muse that they may just be the best parents in the world, right before their own bedtime tranquility is disrupted by their severely panicked offspring) the short concludes with a display of family unity as they all scramble into the same bed together. It closes off with Homer, ever the conscientious family patriarch, attempting to be the voice of reason and reassure his kids that there is nothing out there that they should be afraid of (a few years' worth of character development later and Homer would undoubtedly have been as terrified as his kids in the exact situation and this responsibility would have fallen onto Marge). The very last words, however, go to none other than Maggie, who can be heard gurgling out the titular statement (voice credited to Liz Georges) while the rest of her family slips away into the darkness. This might seem like a curiously cutesy note on which to end such a doggedly unconventional animation. But then the Ullman Simpsons were always too distorted to be particularly cutesy, even when they were affirming that they were, when all is said and done, a pretty loving bunch.

As the shorts continued and Groening's visual style slowly became more polished and assured, the circus freak show element that those early installments had pushed for all it was worth inevitably started to be phased out. To an extent, the Simpsons cast will always be an intrinsically odd-looking bunch, what with their massive bug-like eyes, gaping overbites and neon yellow complexions, but their designs definitely softened and became rounder-looking over the years, making them seem warmer and more approachable, and overall less like the kind of ghoulish creatures you always feared might be lurking down in your grandmother's basement as a kid. Groening was also dead-set on his series maintaining a certain level of fundamental realism, so the early cartoon freakiness of the character mannerisms was likewise ditched. Which is why I find the Ullman shorts so eternally fascinating. They offer glimpses into roads ultimately not taken - among them, a time when the Simpsons universe was every bit as demonically surreal as it was disarming; when making your skin crawl was as high on its agenda as giving your ribs a good tickling. Back when the Simpsons were a family we could all love and relate to, yet also secretly fear would eat us alive if we ever found them prowling underneath our beds at night.

Pleasant dreams, all. Sleep tight, and don't let the bed bugs bite.

Friday, 13 April 2018

Shit That Scared Matt Groening: No. 12 - The Painter and The Pointer

"12. This old Andy Panda cartoon in which Andy makes his dog pose out in the garden for a painting Andy's creating inside the house. The dog keeps getting annoyed by a pesky bee and, in a fury, Andy ties the dog up in an uncomfortable pose with a rope tied to a shotgun aimed at the dog's head. If the dog moves, he'll get his head blown off. Andy Panda goes back inside and sure enough, falls asleep, leaving the dog to be tormented by the bee."

~ "49 Things That Frightened and Disturbed Me When I was a Kid", Matt Groening (Bart Simpson's Treehouse of Horror #1, 1995)

I decided to kick off this "Shit That Scared Matt Groening" series with item no. 12 on Matt's list, in which Matt recalls a traumatic childhood encounter with a relic from the golden age of American animation. Whenever I read Matt's list, this item in particular always jumps out at me, in part due to the intricacy of Matt's description (when compared to the rest of the list), but also the full-blown hellishness of the scenario he describes. I'm reminded of just how amazingly unsettling some of these vintage cartoons can be - by nature, they tend to rely upon warped set-ups, surreal visuals and lashings of sadistic humour, a formula which many a classic from the golden age can certainly swear by. Occasionally, however, they get the balance very wrong, and when that happens you may end up feeling the same levels of stomach-churning discomfort as the young Matt Groening. Worst case scenario, you get a cartoon that perfectly illustrates the dark gulf between what some depraved adult considers knee-slapping hilarity and what to a young, emotionally fragile child is nothing more than an exercise in horror.

First though, some context on what was scaring young Matt. Andy Panda was an anthropomorphic giant panda created by Walter Lantz of Walter Lantz Productions, during his experimental period when he was trying to come up with a new animated lead to follow in the footsteps of Oswald The Lucky Rabbit (the early Walt Disney creation who, due to rights issues, had wound up in the hands of Universal Studios), whose luck was beginning to run dry by the late 1930s. Andy got his first outing in the 1939 short Life Begins for Andy Panda and went onto to feature in a series of shorts released by Universal Pictures (and later United Artists) throughout the 1940s. Before researching for this piece, I have to admit that I was only really vaguely familiar with Andy thanks to his association with Lantz's more infamous creation, Woody Woodpecker (who got his own start as the antagonist of an Andy cartoon, Knock Knock, in 1940, and ultimately wound up replacing Andy as Universal's big animated draw), and so I entered with essentially no prior knowledge of the character and little idea what your typical Andy escapade would entail.

Matt does not actually list the title of the Andy Panda cartoon in question, but after a quick review of Andy Panda titles I deduced that The Painter and The Pointer was likely the short he was referring to. Released in 1944, The Painter and The Pointer opens with Andy attempting to paint a portrait of his dog Butch (who bears a - probably none-too-coincidental - resemblance to Mickey Mouse's more familiar canine cohort, Pluto). Unfortunately, Andy's efforts are hampered by the problem that Butch isn't overly inclined to hold himself in a static pose for long, particularly when there are pesky creepy-crawlies harassing him, and so Andy devises a...shall we say, very draconian solution to keep his dog in place.

Watching The Painter and The Pointer, I noted that Matt had actually misremembered a number of details about the short, although the most disturbing element - Andy tying his dog to a loaded shotgun in the hopes of coercing it to keep still - is pretty much as he describes it. There is, however, no bee in this cartoon. Instead, Butch is initially bothered by a fly, but the main antagonists are a couple of spiders who suppose, somewhat ambitiously, they can wolf down a full-grown pointer, and proceed to attack Butch while he's at his most defenceless. The prospect of being devoured by spiders might strike some viewers as far more hardcore nightmare territory than being pestered by a mere bee, but I'll emphasise that these are very cartoony spiders, with big red noses and fuzzy hairdos. They're actually kind of adorable-looking (although annoyingly they only have six legs - I presume because giving them the fully eight would have made their character designs overly complicated). The smaller of the two spiders, frustrated by his failure to catch the fly from the earlier, spots the tethered Butch down on the ground and immediately thinks that he would make a good meal (possibly because he mistakes the tether for a web and thus takes Butch for spider-food), a scenario that's obviously all kinds of messed up, though the spiders themselves never come off as being much of a direct threat to Butch - rather, the real peril stays firmly with the loaded shotgun pointed at Butch's head, and the possibility that, in manipulating Butch and hoisting him upwards toward their web, the spiders will inadvertently cause it to fire. The showdown between Butch and the spiders plays almost like an inversion on the classic David vs Goliath dynamic, in which the Goliath figure, who under normal circumstances would have no difficulty fending off these pint-sized pests, is here rendered helpless and becomes our underdog.

Andy himself actually has only a minimal presence in this cartoon, the main drama revolving around Butch's struggle with the spiders and the tension as to whether or not the gun will fire. Once Andy has tethered Butch to the gun, he returns to his house to fetch a new canvas, and doesn't reappear until the very end of the short (the detail Groening cites about him falling asleep is another fabrication - we never find out what is keeping Andy so long). Essentially, Andy's only there to provide the set-up for the conflict, after which the short casually brushes him aside. From what brief impressions I'm able to form, however, Andy is an absolute monster. There is something disturbingly incongruous about his entire character - for one thing, he's a giant panda, one of the least threatening-looking members of the animal kingdom, and yet he wears his face in a permanent scowl and pretty much every word of dialogue that spews from his mouth is in aid of brutally hectoring his undeserving dog. What makes things all the more surreal is that Andy sounds like a child; he speaks with a high-pitched, boisterous and distinctly-youthful sounding voice (courtesy of Walter Tetley) that simply doesn't gel with the sheer bitterness he exudes as a character, nor the spine-chilling callousness with which he informs the unfortunate Butch that if he moves, then "BOOM!...no more doggy!" Really, what kind of twisted degenerate willfully risks killing their dog just for the sake of a painting? And then walks away leaving said dog to be hounded by the backyard wildlife? Oh well, Andy's a jerk.

Here's the thing, though. As I was researching for this piece, I discovered that The Painter and The Pointer is actually a real curiosity among Andy Panda's filmography, in that the panda seen in this cartoon isn't even the real Andy. Or, more accurately, he was an attempt by director James "Shamus" Culhane, who also helmed a number of Woody Woodpecker shorts, to reinvent the character and give him a notch more edge. Andy's character design, softer and rounder in previous appearances (in his earliest shorts Andy was depicted as a wide-eyed infant, and humour revolved around the dynamics between himself and his larger, gruffer pop), was here revamped in order to downplay his cuddliness, and his personality was acidified to match. This accounts for why there's something so intrinsically out of whack with Andy's character in The Painter and The Pointer, for he was an amalgamation of elements that simply didn't fit. It's clear that Culhane went a bit too far in his tampering, for the young Matt Groening was far from alone in being weirded out by the results. Michael Samerdyke, writing in his book Cartoon Carnival: A Critical Guide To The Best Cartoons from Warner Brothers, MGM, Walter Lantz and DePatie-Freleng, calls the panda seen in The Painter and The Pointer an "evil twin", observing that Culhane "may have given Woody Woodpecker a much needed shot of zaniness but this cartoon suggests that his touch wasn't particularly suited for Andy Panda." In other words, the bamboo-biting bastard from The Painter and The Pointer is best viewed as Andy's malevolent doppelganger, who wandered in from another dimension, intent on stealthily replacing the panda that audiences were familiar with (once again, that old Twilight Zone episode about the woman at the bus station comes to mind), only the change went down about as smoothly as a tack. The Wikipedia page for Andy Panda claims that Lantz himself was unhappy with what Culhane did to his ursine creation in The Painter and The Pointer, although it currently does not cite a source. Still, the fact that Culhane's changes didn't stick is probably telling - in Andy's subsequent cartoons he'd reverted back to his softer design and characterisation, suggesting that Culhane's experimentation was ultimately deemed too far a romp from the beaten track. The world was not ready for an evil Andy Panda.

(Incidentally, Culhane directed another Andy short, Fish Fry, within the same year, in which Andy retained his genial personality but again found himself largely sidelined by a conflict between a predator and their prey - the real stars of the short are a goldfish Andy purchases at a pet shop and an alley cat who schemes to pick off the fish as Andy carries it home. One gets the impression that Culhane struggled to utilise Andy as a character, which is why he preferred to devote more screen time to the side characters.)

I was intrigued enough to check out more Andy shorts for comparison's sake, and stumbled across Apple Andy (Dick Lundy, 1946), which, appropriately, is about Andy having to resist his baser urges and stave off the toxic influences of the "devil in a white nightgown" when he indulges in the evil crime of apple scrumping. Despite featuring a likeably menacing Satanic panda and a surreal dream sequence in which Andy is visited by a line of dancing apple core-us girls (see what they did there?), I couldn't help but ponder just how tame Andy's fall from grace here feels compared to the horrors his character dished out in The Painter and The Pointer. Whereas that was a really bleak glimpse into the darkness of Andy's soul (or at least that of his distorted mirror image), here he eats a few too many ill-gotten apples and decides to walk the path of righteousness after suffering a mildly hallucinogenic stomach upset. This Andy is very much an innocent still learning to forebear the ills of the world. He's a less disagreeable concoction than the evil Andy from The Painter and The Pointer, although I couldn't help but feel that this sweeter Andy has his limitations as a character too. Outside of Old Nick's contribution, Apple Andy is not an amazingly interesting cartoon - essentially, it's a flatter version of the classic Donald Duck short Donald's Better Self (1938), with the added gimmick that it's all set to a customised rendition of "Up Jumped The Devil". Diverting enough, but I'm not overly surprised that Andy ultimately wound up being usurped by his old woodpecker nemesis.

I am pleased to report that The Painter and The Pointer does not end with Butch still tied in an uncomfortable pose and entirely helpless in the face of an impending arachnid attack (one thing which particularly haunted me about Matt Groening's description was the implication that was all there was to the short, the dog's defencelessness against his tiny tormentor's malice being the final punchline - the thought that the dog was stuck there for potentially all eternity was enough to make my stomach churn), but it's still not exactly the most cathartic of endings, for all that Culhane has just subjected us to. In the end, the gun does fire, but it misses Butch and hits the tree branch the spiders have been hoisting him toward, breaking Butch free of their threads but sending the traumatised pointer into an all-out panic. Andy steps outside to find Butch flailing about desperately, still tethered to the gun, which proceeds to go off with every erratic movement the dog makes. Andy gets his canvas wrecked yet again (which if you ask me is way too mild a comeuppance for his brutality) and angrily chases after Butch as the two spiders look on in frustration. It does somewhat haunt me that Butch never gets free of the gun, and that it's still firing at the end of the short - we can only hope that no innocent bystanders wound up being blasted as a result of Andy Panda's ruthlessness.

Does it frighten and disturb ME?

An angry panda who beats, shoots and leaves, and a hapless pooch who's forced to endure his every malevolent whim? It makes for pretty twisted viewing alright, although I will admit that I kind of liked the spiders. I'm left wondering if their shtick of attempting to lasso prey significantly bigger than themselves - while macabre as sin - had any mileage in it for further shorts. That part is just so eye-bogglingly weird that it seems a shame it had to go to waste.

Sunday, 8 April 2018

Shit That Scared Matt Groening: An Introduction

If you can get hold of a copy of Bart Simpson's Treehouse of Horror Issue 1 (originally published in September 1995) you'll find an intriguing Bongo Beat article written by Simpsons creator Matt Groening entitled "49 Things That Frightened and Disturbed Me When I was a Kid" (note: in the UK this article was published in Issue 33 of The Simpsons Comic in November 1999). Here, Matt takes us on a journey down the deep dark well of childhood fear and the various brushes with terror which kept him lying awake in a cold sweat for many a night throughout his youth. Irrational childhood fear can play a major role in shaping one's adult affinities and preoccupations, so this glimpse into the younger Matt's psyche is fascinating in terms of how we plainly see a few themes that would be prevalent in his later work taking form here - for example, Matt brings up his morbid childhood phobia of robots, a few remnants of which were manifestly transferred over into Bender's character in Futurama. What makes it such an entertaining read, however, is the sheer banality of it all, or rather the manner in which Matt's young, impressionable eyes were able to transform the dull suburban world of mid-century America into the stuff of nightmares. Matt's fears were informed by everything from science fiction B pictures to mundane black and white television, from a kid's eye understanding of the politics of the age (Matt feared commies, but for slightly different reasons to the rest of the US) to the freakier happenings (ostensibly, anyway) within his own neighbourhood and his early encounters with the grislier side of nature, among them his first youthful awakenings to the prevalence of mortality and decay. Nowhere is that expressed more succinctly in Matt's list than in item 24, where he supplies an anecdote about opening up a candy bar to find that a bunch of maggots had gotten there first.

Where this list struck a particularly strong a chord with me on a personal level, however, was at item 26:

"26. Uproarious canned laughter on old TV sitcoms."

MY SOULMATE!

Actually, Matt and I have more in common besides our mutual irrational fear of disembodied laughter. Reading through Matt's list, I notice a very clear pattern, whereby growing up Matt was regularly tormented by an older brother named Mark who evidently enjoyed playing on his anxieties.* Well, snap.

I'm such a great fan of Matt's list that I got to thinking that there was perhaps an entire blog series to be mined from going in search of a selection of these objects of terror and giving my own thoughts and impressions on them and their lingering ability to frighten and disturb. There are of course limits to how many of the items on the list I can revisit for myself. The ones relating to Matt's personal first-hand childhood experiences are obviously impractical - I cannot, for example, check out the rotting beaver carcass Matt stumbled on out in the woods one day when he was nine, and nor would I wish to. But the items relating to popular culture (which make up about half the list) are things that I can certainly take a stab at.

As an endnote, the final item on Matt's list acts the punchline to the entire article, namely, "The realization that most of these memories still haunt me." Which is another thing that makes Matt a man after my own heart. I didn't get over a huge chunk of my own irrational childhood fears so much as log them away quietly at the back of my psyche, enabling them to intermittently surface and give my adult brain a good rattling. Which accounts for a significant proportion of the material that I write within these pages.

* Actually, Matt's older brother Mark comes up three times in the list and there's only one instance where he appears to have been deliberately stoking his younger sibling's fears. I'm pretty certain that there's also a Futurama commentary where Matt talks about his brother Mark looking to terrify him by dressing up as a robot, however.

Saturday, 7 April 2018

Animation Oscar Bite 2017: The one where they all get rabies

89th Academy Awards - 26th February 2017

The contenders: Kubo and the Two Strings, Moana, My Life as a Courgette, The Red Turtle, Zootopia

The winner: Zootopia

The rightful winner: Moana

The barrel-scraper: None

Other Notes:

2017 was a funny old year in that, as with the 2016 ceremony, I thought that all of the nominees for Best Animated Feature were strong but, unlike 2016, the prize wound up going to the film that I personally considered the weakest of the five. Apologies to all you Zootopia fans (or Zootropolis, to my European readers) who champion the film as being right up there with Disney's elite, but for me this was one of the more middling entries from Nu-Renaissance Disney - enjoyable enough, but I honestly didn't love it. Zootopia's victory had, nevertheless, struck me as a foregone conclusion. Using the formula I devised in 2015, I figured that it and Moana were the only two entries that reasonably stood a chance here (although Laika probably had a smidgen more hope than in previous years, given that Kubo and the Two Strings had pulled off the impressive feat of becoming only the second animated film to be nominated for Best Visual Effects, after The Nightmare Before Christmas) and I suspected that Zootopia would ultimately have the edge because a) it made the bigger splash at the box office and b) the whole topicality thing. Zootopia came about at a time when people were starting to feel a mite uneasy about where the world might be headed in light of recent developments, and its attempts to depict interspecies tensions as a metaphor for our own human social prejudices had struck quite a chord back in early 2016.

I'll give Zootopia points for trying. It certainly tries to be smarter than your average anthropomorphic animal flick and consider the ramifications of how a universe populated by humanised animals would actually function, but I'm not sure if it succeeds. For one thing, I'm not a fan of the "mammals only" approach. Really, what's so special about mammals, other than that they tend to be more plush-friendly than most other creatures (with the exception of penguins of course)? There are also no domestic dogs or cats in this world, supposedly because it's meant to be an alternate universe where humans never existed and selective breeding was never a thing. Okay, fine. So why are there sheep then? The film deals with the most obvious question the premise raises - if the predators don't eat the prey animals, then what do they eat? - by not addressing it altogether. And if the predators no longer eat meat, then why are they even called predators? Aren't they bothered by the fact that the word "predator" has other, far more unpleasant connotations? And what of the creatures that fit both bills, like the shrews and the weasel? I also think that the film's social allegory - for which it won so much praise and, as noted, was probably the deciding factor in it taking home the final glory - is clumsily applied, largely because the film can't seem to decide whether the predators are the top brass or the victims of this particular society (in practice, it seems me to me that an animal's status in this universe is largely determined by how big and physically powerful they are - the whole Mr Big thing notwithstanding). Zootopia is a film with lofty ideas that ultimately bites off more than it can chew.

So yeah, apologies to all you Zootopia fans, but I am a card-carrying member of Team Moana. For me, Moana is the modern Disney film to best capture the fun and excitement of the 90s Renaissance while redressing many of that era's shortcomings and making the formula feel fresh and updated. I'll confess that, prior to Moana, my feelings toward Musker and Clements were not especially charitable. As far as I was concerned, their glory days came to a screeching halt when they made Hercules (easily the worst film of the 90s Renaissance), after which they never succeeded in regaining their footing. I love Moana so much that I've quite forgiven Musker and Clements for Hercules and I am genuinely looking forward to seeing what they'll do next (assuming that they do have another project in the pipeline). And I don't mean to turn this into a Hercules whipping session (I did just state that I was pretty much over that, after all) but I'm convinced that the major reason why that film failed is because Musker and Clements' hearts just weren't in it, and it showed - it is a well-documented fact that they made Hercules solely because they needed to appease Disney with one more surefire hit before Katzenberg would allow them to start work on their passion project, Treasure Planet (that didn't exactly work out for them either, but that's another post for another time). The real issue with Hercules has less to do with its lack of fidelity to Greek mythology (although I'd be lying if I said I wasn't a tad cheesed off that they made Hades the bad guy and basically conflated him with Satan) than with its very transparent lack of passion for the stories it's drawing from - to Disney's Hercules, Greek mythology was merely a resource to be pillaged; to be ground up and spat out into something that's like a hamburger (and yes, I stole that analogy from Sting - it's a goodun). It would be wrong to suggest that Moana isn't doing the exact same thing on some level, of course, and I wouldn't doubt for a moment that there are plenty of valid criticisms to be made about the film's handling of Polynesian mythology. Whenever Disney takes another culture and retools it into something they can package into your next Disneyland vacation, it inevitably walks a slippery tightrope. But you know what? I could believe that Musker and Clements genuinely cared about bringing this particular story to life. Moana is a film with a great deal of heart; heart for its characters and heart for its setting. The voice cast are on fine form, the animation is beautiful and the soundtrack is disarming in that most euphoric pop-Broadway Disney tradition. The story does hit a number of familiar Disney beats, but it never feels phoned in, thanks in part to its toothsome affection for the strange and eccentric.

On that note, Moana has Tamatoa, and that counts for a heck of a lot. Forgive me if I completely orgasmed over this character back in late 2016, but Tamatoa is a crab who's voiced by one half of Flight of The Conchords and is based on David Bowie - ie: they combined three of my all-time favourite things into a single character; how was I not going to lap that up? (The Bowie influence was a particularly lovely touch - I was reminded of how Ursula's character in The Little Mermaid was a tribute to Divine, who died in 1988). Right after seeing Moana, I ran all the way to my nearest Disney Store, having decided that the one thing I really needed in my life was a Tamatoa plushie...only to get there and discover that no such product existed; in fact, Tamatoa got hardly any merchandise at all. Oh, but they had plenty of stuff featuring that Pua pig, who was really little more than a glorified extra (we don't even learn if Pua is a boy pig or a girl pig in the movie proper - I only refer to Pua as a "he" because the Moana colouring book does). Yeah, if I had one real nitpick with Moana straight off the bat it was that Pua's entire presence kind of bugged me - in that he was blatantly a leftover from an earlier version of the script that no one could quite bring themselves to sever because he was the most merchandise-friendly thing they had going (it's strange that Maui is shown holding Pua in the promotional poster, when the two characters never actually meet). Truthfully, though, I find it impossible to hold a grudge against something so wretchedly adorable in the long term. The pig is alright with me now.

Kubo and The Two Strings felt like Laika's most ambitious production to date, and it paid off very handsomely (in artistic terms, that is; tragically, the film sank like a stone at the box office). It looks phenomenal, and that nomination for Best Visual Effects was very well-deserved. But if you ask me, the entry leading the way in terms of sheer artistic merit would have to be the Wild Bunch/Ghibli co-production The Red Turtle, which is absolutely breath-taking. Every individual frame of animation in this film had me positively salivating. And it's such a lovely, haunting tale on top of that, dispensing with dialogue to tell the story of a lone shipwreck survivor who finds himself stranded on an island (one which fortunately has a steady crop of avocados) and, unable to escape, slowly comes to terms with his predicament thanks to his relationship with a very unusual turtle. Some moments will have you sobbing your heart out, others are genuinely shocking. In particular, there's a sequence early on in the film where the lead character winds up in an extremely perilous situation that will make your guts writhe just watching. It's an utterly sublime film, yet in some respects not for the faint of heart, combining the beauty and tranquility of its island setting with all the fear, frustration and overwhelming loneliness of a lost soul faced with the likelihood of spending the rest of their life there.

The final nominee, the Swiss-French stop motion feature My Life as a Courgette (or My Life as a Zucchini, to my American readers), focuses on the camaraderie between a group of kids living in a children's home, each having to deal with their own parental loss or abandonment while finding a renewed sense of purpose and identity. It gets my vote for the most emotionally devastating of the five; I'm not exaggerating when I state that I was an absolute wreck by the time the credits started rolling. The animation has a beguilingly colourful charm, reminiscent of pre-school television but with a distinctive, tell-tale roughness to the edges that accentuates the central theme of youngsters who've already witnessed far too much within their short time on Earth. There's a lot of darkness in this film, yet it stays largely beneath the surface (if your kids can read a Jacqueline Wilson novel without feeling too unsettled, then they can probably also cope with the depictions of child abuse and neglect included here); ultimately, it is a hopeful story about characters learning to survive and find their way through trauma and/or bereavement. It is a deceptively small picture (only 66 minutes long) which nevertheless encompasses a great deal of emotional weight, and for that I think it will endure as a favourite among fans of less conventional animations.

The Snub Club:

Pixar's Finding Dory failed to make the cut, which took a few online journalists by surprise, but I think it should be obvious by now that the Academy doesn't think too highly of Pixar's recent descent into sequelitis and has tendency to punish them whenever their contribution for the year is an attempt to expand on one of their established properties (we'll see if The Incredibles 2 fares any better in light of recent changes to the voting process). Back when Finding Dory was first announced, my hopes for the project weren't exactly high, because a) it was very transparently being played as Andrew Stanton's Get Out of Director Jail Free card after that whole John Carter debacle (Stanton himself was quite upfront on this point), b) in the original Finding Nemo Dory's family were brought up purely as the basis of a throwaway gag that I never had any interest in seeing expanded on and c) doing a sequel where you place your comic relief character at the centre never struck me as a particularly good idea. But in the end I liked the film just fine and I'm glad that it exists. It's not a perfect film - it takes a while to get going and that sequence in which our fishy friends are implied to have crossed the entire Pacific Ocean in the blink of an eye (???) is just lazy writing, but once we arrive at the marine institute it does pick up considerably. Was I sore that it didn't make the Oscar cut? Nah - although I do like Finding Dory I can see why it perhaps didn't stand out enough when stacked up against the five contenders above. It's a good film, but it's not really boundary-pushing in the way that the best Pixar films are. It tells a nice, sweet, heartfelt story of the kind that we've seen many times before from Pixar without adding anything amazingly new or different to the mix. I also think the film is somewhat hampered by the necessity of having Marlin and Nemo limp along for the ride, despite the story barely involving them for much of the time.

Meanwhile, 2016 was a busy year for the pimply upstarts at Illumination, who released two pictures, The Secret Life of Pets and Sing!, both of which were trumpeted with such aggressive promotional campaigns that there was no escaping the damned things wherever you were on Earth. The first of these, The Secret Life of Pets, was as cynical and shallow a venture in animated film-making as they come - a film less concerned with constructing a meaningful and coherent story than with shaking the merchandising stick for all it was worth. A few of the mirco skits glimpsed in the teaser (notably, Leonard the head-banging poodle) did had have a winsome kind of charm to them, and I came away thinking that they might have gotten a really excellent film out of the concept had they only managed to make it eighty minutes shorter. As it happens, The Secret Life of Pets is the modern-day animation to most remind me of the Fleischers' 1941 film Mr Bug Goes To Town, in that it plays like a short film extended to feature length by way of a truly insane amount of padding. In place of a strong, well-structured narrative, The Secret Life of Pets substitutes an unsightly tangle of paper-thin story threads, all of which essentially just fart around until the third act, when it suddenly seems to dawn on the film that, "Oh yeah, we probably should start building toward a climax now." Films with meandering plots that are basically little more than string of loosely-connected sketches CAN work - think Monty Python and The Holy Grail - but The Secret Life of Pets certainly doesn't pull it off, perhaps because the characters themselves just aren't that fun to fart around with. Most of the supporting pets wind up being entirely useless and disposable (the pug, the dachshund, the cat and the budgie being the biggest offenders), but then their raison d'être was never really to service the plot but to shift plush toys and cereal boxes (incidentally, the one character whose scenes I actually rather enjoyed was the one apparently not considered important/marketable enough to be featured in any merchandise, and that would be the hawk voiced by Albert Brooks). It doesn't help that the two main dogs are among the worst leads I've ever seen in a children's film, in that they're both really, really unpleasant characters in general. A number of critics likened their dynamic to Woody and Buzz from Toy Story and that's kind of true...had Woody been the self-indulgent dick that Katzenberg had pushed for him to be and Buzz a complete and utter sociopath. Sadly, this odious doggy bag made an absolute killing at the box office, so we could be in for endless sequels featuring these quadrupedal tossers yet.

Compared to The Secret Life of Pets, Sing! is A Star Is Born...and not a disagreeable film on its own terms either. I have no love for the entertainment genre it's spoofing (nor do I give out praise easily to Garth Jennings - I still feel some lingering bitterness for his disastrous treatment of The Hitch-Hiker's Guide To The Galaxy back in 2005), but it juggles the multi-stranded narrative format a lot better than The Secret Life of Pets, and the characters are all basically likeable. Unsurprisingly, there's a lot of emphasis on the film's mixtape soundtrack; Sing! takes it for granted that its audience will appreciate a pop/rock shout-out for entirely its own sake, resulting in a number of awkward moments where it feels as if there should be some kind of punchline, but I'm just not grasping it. (I can see the relevance of having a frog sing "Jump" and a beaver sing "Nine To Five", but what exactly is the joke in having a kangaroo sing "Safety Dance"? Is there a joke? Or how about a giraffe singing "Ben"? Is it that such a large animal would be singing a song about such a tiny one? I'm assuming Jennings did appreciate that that song is about a boy and his pet rat when he decided to have a giraffe perform it?) Still, there's not a whole lot I can really complain about here. Sing! is easy the strongest entry I've seen so far from Illumination, and yet it made less money than Pets because a) life isn't fair and b) that whole Star Wars thing was playing in multiplexes at around the same time.

After scaling back considerably in 2015, DreamWorks Animation released two pictures in 2016 - one of them the third installment to one of their better brainchildren, the other a peculiar attempt to revitalise a kitschy nostalgic toy line comprised of plastic creatures with long fluffy hair, which may or may not have been inspired by the success of the latest My Little Pony revival. Back in late 2016, I made no attempt to hide my general sniffiness toward Trolls - I wasn't overly sold on the new character designs, but most of my snootiness was targeted at the film's voice cast. It wasn't universally bad, and I'm not knocking the likes of Anna Kendrick or Rhys Darby, but when I see endless bus ads informing me that Russell Brand, James Corden and Justin Timberlake are all amassing together in the same feature, my gut instinct tells me to run the other way fast. Nowadays, however, I've actually learned to feel entirely well-disposed toward Trolls, simply because it happens to be the favourite film of both of my nieces, and few things can soften your heart toward a movie quite like seeing how much joy it brings the little ones in your bloodline. (Having said that, on the last occasion I went to visit my nieces, I discovered that, to my deepest, darkest horror, they had discovered the Madagascar movies and, well, there are limits, you know!)

Meanwhile, Blue Sky released Ice Age: Collision Course, the fifth installment in the ridiculously protracted franchise that had long been their go-to for a reliable hunk of box office revenue (overseas, anyway). This year, their luck might just have finally run out, for Collision Course straight-up bombed in the US, and the foreign box office, while not altogether terrible, still represented a significant come-down from previous Ice Age films. Well, what can you say, people just got tired of seeing that stupid squirrel wrestle with an acorn ad nauseam. Unfortunately for Blue Sky, they've kind of always depended on the Ice Age cash cow to keep them afloat, since none of their other films (aside from Rio) have ever made that much of a dent at the box office, so it will be interesting to see how they weather this little setback. Personally, I doubt that this will kill off the Ice Age franchise completely, although I think there may be more of a shift toward smaller DTV projects. Truth be told, Collision Course is pretty inoffensive for the most part, and nowhere near as awful as Continental Drift (they got rid of that time-wasting mole-hedgehog hybrid, which is a step in the right direction), but the world could have lived without it.

R-rated crass com Sausage Party apparently fancied its chances as a serious Oscar contender - Sony Pictures gifted it with a lavish awards campaign, on the basis that, "Academy members...want to recognise bold, original and risky breakthroughs." I was never entirely certain if they were being serious or not. Regardless, Sausage Party always struck me as being far more smug and pleased with itself than it had any cause to be. It was a film based purely on novelty, and the trailer had already taken its central joke (it's like Toy Story, but with talking junk food!) about as far as it could go. Honestly, the fact that the trailer was accidentally played before a screening of Finding Dory felt like the best possible punchline to this entire conceit in itself - lord knows, we didn't need the actual film to exist on top of that. If I wanted a freaky CG feature that takes on organised religion and champions sexual liberty...I've already got Happy Feet, thanks.

Afterword:

When I started this retrospective, my initial thoughts were that I might conclude by ranking all of the winners to date from Best to Worst. That was when I hoped that I might get it finished before the 90th Academy Awards (which was always extremely ambitious of me, and became damned near-impossible once I'd added The Snub Club section). Now that that ceremony has been and gone, I figure that I might as well wait until I've covered the 2018 nominees, so that I can include Coco in my list. Unfortunately, that'll all have to be put aside until I've had a chance to see The Breadwinner, and for now I can't say when that will be. We'll wrap this up at a later date - in the meantime, revisiting so many animated features has certainly been exhausting, but a lot of fun.

Thursday, 29 March 2018

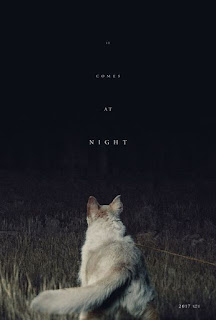

Nothing In The Dark?: The Diurnal Horrors of "It Comes At Night"

Before we start, be warned that this entry contains major spoilers for the film It Comes At Night. In the past, I have discussed the plot details of numerous feature films quite freely on The Spirochaete Trail, although seldom any as recent as this, and as such I feel honour-bound to emphasise right from the go that we'll be wading through serious spoiler territory here. If you haven't seen It Comes At Night and wish to keep your experience fresh, you'd best be clicking your way out post-haste.

Among other things, It Comes At Night, the sophomore film of Krisha-director Trey Edward Shults, was an exercise in how deceptively one could package a feature to make it look like a completely different beast altogether. Audiences who flocked to their local theatres the in summer of 2017 expecting a good old-fashioned horror flick about a family being menaced by a strange nocturnal entity were sorely disappointed to instead receive a small-scale domestic drama (albeit one set in a post-apocalyptic landscape) about a couple of families bickering. The disparity between the film's critical reception and the audience reaction (it currently sits at 88% on Rotten Tomatoes, but earned a D grade from CinemaScore) would suggest that the latter weren't too impressed by this act of bait-and-switch (I can sympathise with that, for I have not forgotten the sheer embarrassment of attending a screening of M Night Shyamalan's The Village, which made a similar gambit, back in 2004). At the heart of the problem is Shults' rather befuddling choice of title, which to the rookie oozes intrigue, but may leave those who have seen the film scratching their heads, or else thumping their fists in frustration - at the very least, it's hard not to come away with the impression that Shults conceived the title before he'd fully ironed out the details of his story. What, precisely, comes at night? Add that to the film's misleading marketing campaign, which hinted strongly at the supernatural but drew heavily from surreal dream sequences experienced by the lead character, and you had a feature all but guaranteed to leave a sour taste in the mouths of a good percentage of its viewers. Is Shults' film a work of fraud, a barrage of cheap tricks that promises much but delivers little, or is there actually a deeper puzzle here to be solved?

It Comes At Night concerns a family who live in seclusion in a house buried deep in the forest; a house that could easily pass for a reasonably cosy holiday home, aside from the ominously-coded red door which provides its only passage to and from the outside world. It becomes apparent that the family are actually surviving in a tiny, hidden pocket of a world where civilisation has crumbled following the outbreak of a highly infectious disease, the symptoms of which include heavy vomiting, furuncles forming in the skin and, most unnervingly, a blackening of the eyes. In the opening scene, parents Paul (Joel Edgerton) and Sarah (Carmen Ejogo) are at the point of having to euthanise the latter's father, Bud (David Pendleton), who has come down with the disease, an act in which their teenage son Travis (Kelvin Harrison Jr) is required to participate. In the aftermath, Travis is haunted by visions of his ailing grandfather, and seeks solace in the companionship of Bud's beloved dog, Stanley. Later, another family living in the vicinity - young parents Will (Christopher Abbott) and Kim (Riley Keough) and their five-year-old son Andrew (Griffin Robert Faulkner) - make their presence known and the two families form an uneasy alliance in which they all have share of the house in the hopes of being stronger together. The household obeys a strict set of rules, including that they never go out at night and do not go out in daylight unaccompanied. For a time this arrangement works, but when Stanley the dog becomes agitated about something in the woods and disappears chasing after it, only to later return at death's door, a chain of events is set in motion causing the alliance to break down. The characters begin to suspect that one of them may have brought the infection into the house, bringing tensions between the two families to a head and leading, inevitably, to tragedy. In the end, nothing in particular comes at night, and the only tangible external threat that manifests itself at any point are two unidentified men (Chase Joilet and Mick O'Rourke) who attack Paul and Will early on the film. There are no witches, zombies or demons lurking in these woods, just the ugliness of humanity under pressure.

There are no traditional monsters in It Comes At Night, although if you are determined to see one, then odds are that you probably will. I've seen some viewers propose that the characters are actually in the midst of a zombie apocalypse with no zombies in sight - that this is the true nature of the disease and why the family make a strict point of burning the bodies of the infected, and that the outside world is menaced by sleepwalking zombies on a nightly basis (my take: that's an awful stretch. It was always straightforward enough to me that the family burn bodies to prevent the spread of a highly infectious disease). Others insist that if you watch carefully enough, you can make out the ominous form of a distinctly non-human creature lurking the backdrop during the sequence where Paul is driving away from the house with Will. I can see the appeal of this claim - it (allegedly) occurs during a moment where Paul's anxieties are fixed squarely on Will, the implication being that Paul is so preoccupied with whether or not he should trust this strange intruder that he fails to spot the actual monster lurking in plain sight. But I pooh-pooh it nonetheless. Unless Shults cares to confirm otherwise, I'm inclined to see this as another variation on the "munchkin suicide" legend that plagued The Wizard of Oz for many decades. People see a monster through the power of suggestion, not because there's actually a monster there. Having studied the moment in question closely in slo-mo, I'm confident that all we're actually seeing are the rotting remains of a dead tree. (Besides, if we are looking at "It" in this particular sequence, then It appears to be violating the rule made explicit in the title - more on that point later).

Nothing to see here.

In lieu of any literal monsters, our most logical explanation would be that the "It" of the title refers to something altogether less tangible, something nestled deep within our human nature. Perhaps it is all as simple as fear itself that comes at night, which seems borne out in Travis's darkest, most terrible fantasies taking on a monstrous life of their own whenever the lights go out. Some viewers have condemned the film's extensive focus on Travis's nightly fantasy life as one of Shults' biggest cheats, in that it provides him with enough spooky material to fill out a trailer and package the film as more traditional horror fare, while having little direct bearing on how the plot is resolved. In some cases, these fantasies might be seen as totals teases, hinting at plot directions that are otherwise left untouched. In one such sequence, Travis breaks the household's cardinal rule and goes outside at night in an effort to locate the missing Stanley, only to run into an object (unrevealed to the audience) of pure terror, yet the film isn't much interested in what lurks beyond the walls of the shelter at night, or in forcing the characters out to traverse this forbidden zone. We might have assumed that such a plot point was telegraphed early on when Paul stated that there are certain circumstances, "real emergencies", in which they might be made to go outside, but it does not occur. In a way, Travis's fantasy seems thrown in as a substitute for any actual representation of the outside world at night, which barely features at all - nearly all of the nocturnal scenes taken place within the confines of the domestic space, the drama deriving from the occupants' mutual suspicions of one another. For the most part, It Comes At Night does not go The Blair Witch Project route, in which the characters are menaced by a malignant presence that always keeps itself just slightly off of camera. By the end of the film, the very worst atrocities have been committed by the central cast on one another, and we are left pondering whether, if there did just happen to be something out there in the woods all along that had it in for these humans, it ever had to lift much of a finger (or equivalent appendage), for humankind will obligingly cannibalise itself given the right provocation.